Mary Ellen Lepionka

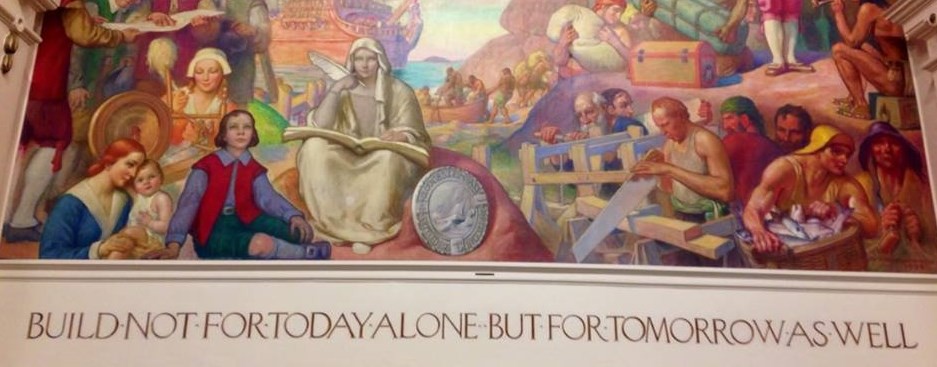

Frederick Mulhaupt (1871-1938) painted “Native American Life on Cape Ann” for the old Maplewood School in 1934. It was later moved to its current location at the O’Maley Middle School.

Erasure narratives, in which the Indians disappeared, reached even into science. Many early archaeologists and ethnologists believed that New England Indians were of little interest or consequence, not worthy of study. Archaeological sites in New England consisted only of shell heaps and burial grounds, paling in comparison to the monumental architectures of the Native civilizations of Mexico and South America. But the more the Indians were thought to have disappeared, the more people began to lament their loss. The “vanished Indian” was invented, and New Englanders began to exploit, and distort their memory. In the process, they misappropriated Native culture and identity.

Impersonating Indians and dressing up as Puritans and Indians became fashionable around the turn of the century. The history of English-Native relations had been reduced to iconic moments—deed signings and massacres. In the celebration of Gloucester’s 250th anniversary in 1892, Robert Pringle designed four horse-drawn floats with costumed actors frozen in significant poses: Samuel de Champlain warily greeting the Pawtucket on Rocky Neck in 1606; Roger Conant arbitrating the feud between Captain Hewes and Myles Standish on Fisherman’s Field in 1625; Samuel English, the “Last Sagamore of Agawam”, deeding Gloucester to the English in 1701; and Gloucester militiamen drawn up against the British in the War of Independence. Pringle also had a Myles Standish—diminutive red-bearded soldier with fiery temper and Napoleonic hauteur—circulating through the throngs of thrilled spectators with “Puritans and Savages” in tow.

Bicentennial celebrations throughout the Northeast included speeches in honor of someone in the community identified as the last Indian. In the 1890s Zerviah Gould Mitchell of Lakeville was billed as the “Last of the Wampanoags”, for example, despite the fact that she (a) was Mahican, not Wampanoag, and (b) had two daughters with descendants whose descendants are living to this day. Her designation as the last had to do with the concept of racial purity. To be authentically Indian you had to be pure-blooded.

Believing there were no more pure-blooded Indians left east of the Appalachians, beginning in the mid-19th century New Englanders developed a nostalgic, romantic craze for them. We got Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Hiawatha”, the Last of the Mohicans by James Fennimore Cooper, and “The Bridal of Pennacook” by John Greenleaf Whittier. Henry David Thoreau canoed up the Concord and Merrimack. Monuments were erected in town parks throughout the Northeast in memory of famous Indians—Uncas, Canonicus, Miantonomo, Masconomet, Samoset, Squanto, Massasoit. Streets are named after them in Winniahdin (“In the vicinity of the heights”), a neighborhood on Little River in West Gloucester developed in the 1890s as a summer colony. No less than twelve statues of Massasoit stand in twelve different cities and towns, all eager to claim him for their own.

By 1900 it became popular to impersonate Indians on stage as well as in parades, in addition to writing romantic fiction harking back to the days when there were Indians. Most notably, the famous actor Edwin Forrest played Metamora, “the Last Wampanoag” in a melodrama about the vanished Indians. Metamora toured internationally and was a sellout equivalent to Hamilton today.

Appropriations of Native identity were not new. Pocahontas, for example, first appears in a 17th-century engraving by Simon de Passe as a dour Englishwoman-by-marriage (to John Rolfe in Virginia Colony). Then, in an anonymous 19th-century etching she is a chaste but ravishing (or ravished) beauty holding a calumet (peace pipe). Now, in a 21st century Disney cel she appears as a competent, liberated, athletic (but still sexy) girl. As in Snow White, forest animals and little birds adore her.

The acme (or perhaps the nadir) of appropriation was the Improved Order of Red Men (IORM), a fraternal organization and secret society for white men that spread in the late 19th century. Their stated intentions were to preserve beliefs and values of the vanished Indian and his way of life. It involved organizing as a tribe, meeting at council fires, and dressing up as Indians. Until the mid-1900s actual Indians, blacks, those of mixed race, immigrants, and the unemployed were not allowed to join.

On parade in Gloucester’s 250th anniversary celebration in 1892 were IORM Wingaersheek Tribe No. 12 of Gloucester, Wonasquam Tribe No. 23 and Winnekoma Council Daughters of Pocahontas No. 41 of Rockport, Chebacco Tribe No. 93 of Ipswich, Ontario Tribe No. 103 of Wenham, Manataug Tribe No. 1 of Marblehead, Naumkeag Tribe No. 3 of Salem, Masconomo Tribe No. 11 of Peabody, Chickataubut Tribe No. 13 of Beverly, Passaqui Tribe No. 27 of Haverhill, Taratine Tribe No. 24 of Swampscott, and three tribes from Lynn: Sagamore Tribe No. 2, Winnepurkit Tribe No. 55, and Poquanum Tribe No. 105. In “Degree of Pocahontas” parade floats, white women in the IORM women’s axillary impersonated squaws.

The Improved Order of Red Men

The Red Men remained active on Cape Ann—I remember them in parades when I was a child—perhaps you do too–with black braided wigs, mysterious loincloths, bloodied tomahawks. They made war whoops, and we would shriek. They would prowl on the fringes of parades and menace onlookers, pretending to scalp the boys at the curb, taking pretty girls captive. They would reach into the crowd and grab the girl, tie her hands or put a rope around her neck, and force her to walk a ways in the parade before letting her escape. (I shudder now to recall how badly I wanted to be that girl.)

The IORM movement did not start to wane until the 1950s as the American Indian Movement began. Wingaersheek Tribe No.12 of Gloucester was not officially disbanded until 2009. Participants thought they were preserving the best of authentic Native American culture when they more often were passing on distorted and mythologized interpretations of Native history and culture and perpetuating the narratives of erasure. The wrong stories and stereotypes even became enshrined in our social institutions. Charles Allan Winter’s beautiful mural in Kyrouz Auditorium in Gloucester City Hall, created in 1934—the masthead for “Enduring Gloucester”—features a solitary seated “naked” Indian smoking a peace pipe, no doubt representing legendary Pawtucket neutrality toward the English throughout Agawam during the colonial period.

Elsewhere in City Hall, Frederick Mulhaupt’s mural misrepresents the Indians while meaning to commemorate them as a part of Gloucester’s history. No Pawtucket ever dressed like that or had pots and blankets decorated thus, nor did they ever conduct trade with Vikings. (Actually, there is not a shred of evidence that Northmen ever set foot here, and Thorvald is not buried on the Back Shore. Robert Pringle and others promulgated this idea during the Viking craze of the 1890s, while earlier histories of Cape Ann do not mention them at all—but that is another whole story.)

Meanwhile, Mulhaupt can be forgiven for artistic license and not knowing better. We must all be forgiven, I think. We are all products of our time and place and cannot be held accountable for what happened in the past. Plus, most people in any time and place don’t really know what’s happening to them most of the time or understand how their actions and beliefs are shaping human history. We can only be responsible for how we respond once we figure it out. As FDR says in the legend under the Kyrouz Auditorium mural, we must build for tomorrow.

Pocahontas (1910 silent film)

In our special place that is Gloucester, over the sweep of time, I see that in the first hundred years of contact colonists’ admiration for Native Americans as noble savages was replaced by fears of Englishmen becoming savages themselves and by derogatory views of Indians. The red man became the white man’s enemy and after that the white man’s burden as conquered people. Over the next hundred years, the narratives of erasure were written and acted upon. Then in the hundred years following their “disappearance”, Native Americans were remembered, lionized, impersonated. Native identity was appropriated and they became romantic heroes and victims in literature and in art. In the last 50 years New England Indians have been rediscovered as not so vanished after all, nor so romantic. I wonder what the next 50 years will bring.

Many Native Americans today are politically active. They have been risking rediscovering and redefining who they are–intent on language revival, cultural preservation, and the reconstitution of true communities, incorporating western as well as eastern expressions of Native culture. As a scientist and historian, I see great interest and consequence in this enterprise, certainly worthy of study. I think all our early literatures need to be reread, our histories rewritten, and new narratives put together for more accurate, integrated, truths. I wonder what that would look like—a history that integrates colonial and Native lives and events. Hmmm….

Cigar Store Indian Princess. Courtesy of Cape Ann Museum

Unknown Carver c. 1855

On display at H. C. Brown Tobacco Shop, Gloucester, from 1905 to 1945.

Mary Ellen Lepionka lives in East Gloucester and is studying the history of Cape Ann from the Ice Age to around 1700 A.D. for a book on the subject. She is a retired publisher, author, editor, textbook developer, and college instructor with degrees in anthropology. She studied at Boston University and the University of British Columbia and has performed archaeology in Ipswich, MA, Botswana, Africa, and at Pole Hill in Gloucester, MA. Mary Ellen is a trustee of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society and serves on the Gloucester Historical Commission.

Mary Ellen Lepionka lives in East Gloucester and is studying the history of Cape Ann from the Ice Age to around 1700 A.D. for a book on the subject. She is a retired publisher, author, editor, textbook developer, and college instructor with degrees in anthropology. She studied at Boston University and the University of British Columbia and has performed archaeology in Ipswich, MA, Botswana, Africa, and at Pole Hill in Gloucester, MA. Mary Ellen is a trustee of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society and serves on the Gloucester Historical Commission.

Excellent essay! But I think it’s James, not Robert, Pringle. Or was Robert another character altogether?

LikeLike

How should the native Indians be commemorated? The romanticized view helped dispel the skulking enemy in the forest. Certain Indians did become part of our history and lacking real representation, must be imagined as do white women of the time like Martha Winthrop and Anne Bradstreet. Aren’t our legends as much a part of who we are as reality, which in itself is uncertain?

LikeLike

Not just “certain” native Americans(we now know europeans landed in the Americas not India so lets address them correctly) but all the Natives that occupied this land our part of our history. Without them European survival was doubtful and they were the first to be here. There is so much Native American culture around that people are blind to because of this appropriation. They have been carried through history with us and to commemorate them is the LEAST we can do to honor their memory as they were violently wiped out through massacres, rapings, and biological warfare. I would say in order to pay homage simply by mourning them, take away celebrations that celebrate extinction and oppression of other people like thanksgiving, 4th of July, etc. Celebrate brown people! fight for brown people, spread the TRUTH that capitalism feeds off hiding, etc etc

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Historic Ipswich and commented:

By Mary Ellen Lepionka courtesy of Enduring Gloucester

LikeLike

thank you for sharing and taking the time to research our ‘lost’ history. I’m Mexican American- Native American blood de Mexico but born and raised in Gloucester. Many white people don’t understand why it angers me when I’m asked “oh are you from here?”(assuming that I’m not)- its a constant reminder of the erasure of my ancestors and the lack of brownness around me, quite isolating. the ignorance in the question alone is dumbfounding. I believe this is why many people of color that are born here become whitewashed and ignorant(not everyone but I know a handful- and Gloucester’s pretty white). When there is no representation, the hate is internalized. these are all reasons why we need to reread documents and such like you said because the truth is lost, and constructed into a narrative that fuels white supremacy. we need to listen to one another!

LikeLike