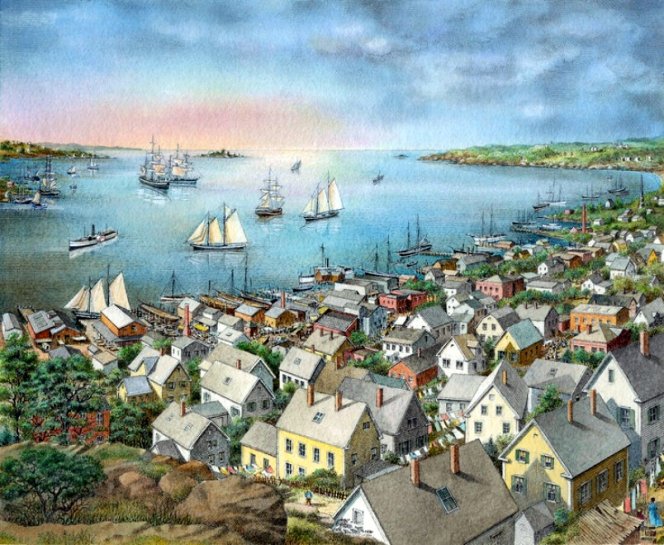

Gloucester Gone By © Laszlo Kubinyi

The McCarthy Debate

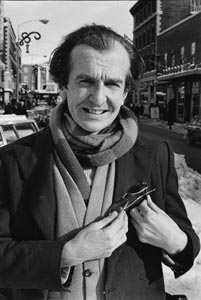

Peter Anastas

In the spring of 1953, our Gloucester High School history club held a debate about the anti-communist crusade of Senator Joseph McCarthy. As a sophomore, I had little understanding of politics and I knew less about communism. Yet, I voluntarily argued on the side that favored the junior senator from Wisconsin’s red-baiting tactics.

At the time of the debate Dwight Eisenhower was president, the Cold War heating up. We had recently concluded Harry Truman’s unsatisfactory “police action” in Korea, a prelude to the war in Vietnam, both in terms of the way the war was fought and the manner in which it was sold to the American people. After Korea, the sense of relief and victory that swept through the nation following the Second World War had turned into a mood of defeat, if not outright paranoia, as our leaders pressed upon us the need to combat “the Communist menace,” at home and abroad.

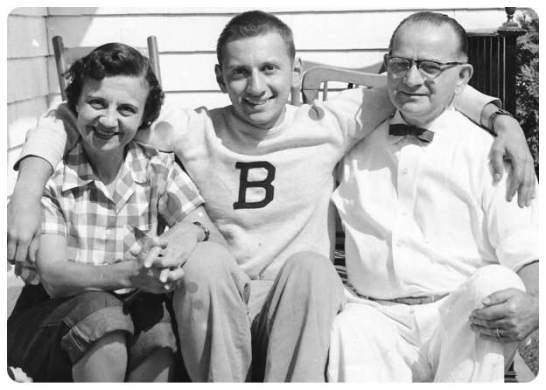

My parents had once voted for FDR, whom my father idolized; but like many immigrant families, who began to prosper in their new country, they were inherently conservative. They favored Eisenhower for president over the urbane and sophisticated Adlai Stevenson, not only because they were enthralled by Eisenhower as the great general and father figure, who had played a major role in winning the war for us, but also because they didn’t want to seem out of the mainstream of this new American life they believed had been good to them.

Peter and parents

Eisenhower was the hero in our family, as he was in many middle-and working-class homes. But McCarthy was a different phenomenon. You couldn’t turn the TV on without seeing his scowling face and slicked back hair, his snarling insistence on “point of order” in any congressional debate or committee hearing.

Although the upstart senator soon proved to be a drunken bully, many Americans of goodwill fell for his anti-communist crusade, as McCarthy attempted to “rout out” putative communists and “communist sympathizers” in the government, feeding a national hysteria, during the course of which teachers, who were thought to have held “subversive” opinions, or to have been “card carrying” members of the Communist Party, or even “fellow travelers,” were driven from their jobs, while Hollywood instituted its infamous Black List, under which many actors, writers and film professionals, who were believed to have had a left-wing history, were prevented from working in the industry.

One of the ways this hysteria played out in small towns like Gloucester was that our parents would constantly be asking us if we had any teachers we thought might be communists. They demanded to know what we were being taught and, especially, if our teachers expressed any “extreme” or “radical” opinions, which they might be trying to impress on their students.

Anti-communism was in the air when I was fifteen years old and McCarthy had not yet taken on the Army and been silenced, if not humiliated, by their attorney Joseph Welch during a famous exchange in which Welch commented, “Until this moment, Senator, I think I never gauged your cruelty or recklessness…You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?”

Joe McCarthy and Roy Cohn

That hearing concluded on June 30, 1954, after which the country, having tolerated McCarthy’s scurrilous behavior on TV for several years, began decisively to turn against him. On December 2, 1954, the senate voted to censure McCarthy, effectively terminating his influence and his career.

All this happened after our history club debate, so that when the debate occurred McCarthy was still a powerful figure, at least in the popular mind. Among many other students, our classmate Bob Stephenson was known for his anti-communism. Bob’s father had been a member of the diplomatic corps. After his death, Bob’s mother, whose family had been lighthouse keepers along the New England coast, brought Bob and his brother home to Gloucester. The Stephenson’s lived in a small, yellow 19th century house on Mansfield Street, with a green picket fence and an ample backyard. Over their front door was a green-painted sign in the form of a metal circle around the inside of which were positioned three legs. Bob described it to us as being a “triskelion,” the official symbol of the Isle of Man, having its origins in Medieval Sicily.

His parents had obtained it while vacationing on the British island. It became one of many artifacts his mother showed Bob’s friends when they visited, including beautifully woven red and white striped Central American serapes and a gourd with a silver straw from which yerba mate tea was sipped in Paraguay, where Bob’s father had once been stationed. These artifacts, along with a number of landscape paintings and photographs of places where the family had traveled during Bob’s father’s postings, lent an exotic atmosphere to Bob’s house.

Bob’s mother Cora was a woman of strong opinions to whom my mother deferred because, as she’d say, “the Stephenson’s have traveled a great deal.” She disliked Democrats, even finding Eisenhower too liberal, and would be constantly on guard lest her two sons be indoctrinated by what she called “free-thinking teachers.”

Bob echoed his mother’s views, along with his own brand of subtle but extremely mordant humor, while his quiet brother chose the sea as his calling. It would be convenient to claim Bob’s influence in my choice of sides in the McCarthy debate; but in reality I came to my own decision about McCarthy, having discovered a book in pulp format among the magazines on my father’s newsstand. It was McCarthyism: The Fight for America, published in 1952 by Devin Adair and written by none other than the senator himself.

No McCarthyite, my father offered me the book to read, when he saw me flipping through the cheaply printed edition. I took it upstairs to my room and by the end of a summer afternoon I had read all of its 101 pages, interspersed with grainy newspaper photographs of the senator in his characteristic stance, before a microphone, a sheaf of papers in his left hand, presumably containing the names of the requisite number of communists he had lately discovered to be in the employ of some department of the United States government. The numbers seemed to change from week to week, if not daily.

However, it wasn’t the numbers that attracted me to McCarthy’s crusade; and it certainly wasn’t the man himself in his oily, rumpled-suited presence. It was the stories the book contained, stories of how the American Communist Party, under the alleged control of Soviet Russia, had “infiltrated” every level of national life. This was also the era of the televised Cold War anti-communist series “I Led Three Lives,” the presumed story of Herbert Philbrick, who by day was an advertising executive in Boston, while by night he doubled as an undercover agent and a counter-spy.

Philbrick had infiltrated the American Communist Party on behalf of the FBI in the 1940s and written a bestselling book on the topic— I Led Three Lives: Citizen, ‘Communist’, Counterspy (1952). The series premiered in 1952, a year before I read McCarthy’s book, which influenced the stand I took in our history club debate. So for me there was a certain amount of intrigue in the drama of those who operated secretly, both on behalf of democracy, as I then believed, and against what I also assumed to be the dangers of communism.

I didn’t know a great deal about McCarthy as I entered the debate, and I understood far less about Marxism (it wasn’t until a year later that I read The Communist Manifesto and found it compelling, as workers were exhorted to throw off their chains and transform the world). Before the debate, my head was filled with slogans and with arguments I’d heard from Bob and his mother. As for myself, I couldn’t even define “totalitarianism.”

None the less, Bob and I volunteered to present the case for McCarthy. Our opponents were Laszlo Kubinyi and Bruno Modica. Laszlo’s parents were ceramic artists, who owned a gallery at the opposite end of Rocky Neck from Dad’s luncheonette. While the Kubinyis had lived for some years in Gloucester, Bruno and his family had recently arrived from Genoa. His father was an engineer in a fish processing plant on the waterfront, and his mother, once Bruno and his sister had gone off to college, began to teach Italian at the high school’s adult education center. Laszlo played drums, and Bruno, like most young Italians I would come to meet nearly a decade later, had a passion for current events, especially for politics.

All four of us sat at a long table in front of the history classroom in which the club met monthly. The debate was monitored by the club’s president, Lincoln Higgins. Our faculty advisor, the department chair, Miss Hammond, stood by to see that we all observed the proper debating procedure.

I was wearing a gray tweed sport jacket, a starched white dress shirt and one of my father’s Haband neckties; Bob was dressed similarly, except that he favored a maroon corduroy jacket. Bruno, whose coal black hair was always beautifully cut, wore tailored Italian suits that we would die to have owned, while Laszlo, though he obeyed the dress code of jacket, tie and slacks for boys, wore his hair longer than most of the boys, even those who slicked theirs back into DAs.

The question up for debate was whether McCarthy’s tactics were acceptable and whether or not they served the purpose of exposing those who were thought to be a menace to American democracy. Bob and I argued in favor, while Bruno and Laszlo argued against us. They were far better prepared than we were, and they argued more soundly. As the debate progressed, I knew that Bob and I had lost because we really didn’t put forth cogent arguments based on carefully articulated critical distinctions. Instead, we relied on exactly the kinds of pat slogans, clichés and emotional outbursts that the McCarthyites employed—“Well, how do we defend ourselves against those for whom everything is a means to an end?” “Would you like to wake up one morning and find the country taken over by communists?”

In contrast, Bruno and Laszlo quoted from magazine and newspaper articles and editorials, and from the testimony of those who had suffered under McCarthy. They recounted the story of Owen Lattimore, a leading American scholar of Asia, who had been slandered as a “top Russian spy” by McCarthy; and they described Richard Nixon’s attack on congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, against whom Nixon ran for the senate in California, calling her “The Pink Lady” for her supposed communist friends and supporters. They spoke eloquently about First Amendment Rights, about free speech and freedom of association. They particularly stressed that, as of the moment of our debate, not a single one of McCarthy’s allegations had been found to have substance.

But when it came time for the club members to vote on which side had prevailed, the students overwhelmingly chose Bob and me. Once the debate was over, I knew I’d been mistaken in taking McCarthy’s side. My position in the debate and the club’s vote against Laszlo and Bruno created a chill in our friendships. Miss Hammond said nothing; but when I later studied American history with her, I could tell from her teaching and the texts she selected for us to read that she was no right-winger.

Graduating from high school, Bob studied art in Boston before initiating a career in military intelligence that took him over most of the world. He mastered several languages, including German and Arabic, returning to Gloucester after his retirement to resume work as an artist in a Zen-like studio just off Main Street, overlooking the harbor. His magic-realist paintings of the city and the waterfront seemed to incorporate the imagery of the cultures he’d come to know intimately.

He never lost his fine sense of humor, which, if anything, had become darker over the years. Nor had his politics changed—he once visited me in Florence, claiming to friends back home that he’d come to save me from Italian communism.

Peter and Bob in Florence. 1959

Bruno went to Brown University, after which he entered the world of international business, serving in executive capacities for multinational corporations in Italy, France and Belgium. Laszlo played drums in my brother Tom’s big band during their final years of high school, and later in New York. Tom and I were invited to some lively parties in the rambling family house near Cressey’s Beach, gatherings at which Laszlo’s parents danced Hungarian folk dances and served delicious food. After high school Laszlo attended the Museum School in Boston, followed by a career as a prolific illustrator, artist and author of children’s books.

As for me, I became an activist in the 1960s, while the war in Vietnam raged—going to teach-ins with my students and attending anti-war demonstrations. In a word, everything that McCarthy would have abjured.

In Memoriam

Bruno Modica passed away on Tuesday, December, 11, 2012, in Sun City Center, FL. from complications of Parkinson’s disease. Bob Stephenson died on Sunday, August 9, 2015, in Seacoast Nursing and Rehabilitation Center, Gloucester, after a brief illness.

(This is a chapter from Peter Anastas’ recently completed memoir, From Gloucester Out.)

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.