The Art of Winslow Wilson/Pico Miran opened on June 8 at RAA&M and will remain on view until July 8, 2019

by Peter Anastas

Woman with a White Collar (Winslow Wilson)

During the summers of 1956 and ‘57, I had my first job in journalism editing the Cape Ann Summer Sun, a weekly eight-page supplement to the Gloucester Daily Times. Drawn to contemporary art, I often reviewed the shows of the Cape Ann Society of Modern Artists (CASMA), whose gallery was located in the old Red Men’s Hall in Rockport. While covering the exhibitions of what was then considered controversial art (compared to the traditionalism of most Cape Ann painting), I became interested in the work of an artist who called himself Pico Miran. Whenever the occasion arose, I wrote about his paintings, which I felt were uniquely distinct from the rest of the work displayed at CASMA. It turned out that Pico Miran had another name – his real name – Arthur ‘Winslow’ Wilson. A native of Texas, Wilson had been a classmate of poet E. E. Cummings at Harvard in 1911-1915. After college and the war (Wilson served in the Air Force, Cummings drove an ambulance), they moved to Paris in 1923 to paint and then back again to New York, where, for a time, they shared a studio in the Village.

Cummings was one of our finest early Modernist poets, as well as a considerable painter himself. Wilson, who retained a studio in New York and another on Cape Ann, beginning in the 1940s, taught portrait and landscape painting classes at the Rockport Art Association for many years in addition to exhibiting portraits and seascapes at RAA, as well as nationally. Wilson also produced a radically different kind of painting, which – in a catalog for a 1951 exhibition of his work at the American Art Gallery in New York – he called “Post-modern art,” employing a term which the poet Charles Olson brought into currency at the same time. In his catalog essay for the exhibition, Wilson wrote: “The new art will be Gothic American, in the sense that it will brush aside all soft precedent in the whole life span of art, and treat forbidden truth, and be moltenly ductile to the shape of realities never before considered proper for painting.” Wilson showed this highly experimental new work at CASMA, under the name Pico Miran.

At first glance, one might consider the paintings inspired by Surrealism; but Wilson-Miran eschewed the term. “My drawing is straight classical naturalism,” he wrote in a letter to the editor of the Gloucester Times during the summer of 1956, “the very kind that surrealists have violently rejected…. My art has no relation to that of Salvador Dali, whom I knew in Paris.”

Ectoplasmic brain remembering its own skull (Pico Miran)

Wilson liked my attempts to understand his “Pico Miran” paintings and he wrote a further letter to the editor indicating his appreciation. I responded to Wilson’s letter and we exchanged several communications before he invited me to his studio in the Bradford Building on Main Street. What I discovered was a conventionally dressed older man, with thinning hair and a brown beret. He ushered me into his sparsely furnished two room apartment in an old Gloucester redbrick downtown building that would sadly be demolished after a fire in the early 1960s, a conflagration in which Wilson lost the only copy of an autobiography he had been working on. We sat in a wood-paneled front room. There were no paintings in evidence. He gestured at the door to another room where, he said, he painted. At the time I did not know that Winslow Wilson and Pico Miran were the same person.

As we sat and talked in the room that smelled faintly of turpentine and linseed oil, he told me about his friendship with Cummings, with whom he was still in touch. He asked me if I had read anything by Samuel Beckett and I told him I had read Waiting for Godot and Beckett’s trilogy of novels. Wilson responded that living in the Bradford building among single old men was like inhabiting a Beckett novel or play. He also told me that he had been corresponding for some time with the American philosopher and critic Kenneth Burke, who told Wilson, “You sure can make with the paint!”

Wilson’s conversation was as literate and knowledgeable as his letters. He explained to me that one of the themes that lay behind his paintings was the fear of a nuclear holocaust and its subsequent annihilation of all forms of life. He said it was the reigning anxiety of our age and that Beckett’s novels, written in French during the war, were the primary art of our post-war, post-atomic bomb world, reflected in the title of his painting, Apocalyptic Galaxy with the Little Doors to Nowhere.

Apocalyptic Galaxy with the Little Doors to Nowhere (Pico Miran)

Over the next several years, Wilson and I corresponded. He sent me two books by Kenneth Burke, Permanence and Change and Philosophy of Literary Form, which had a significant impact on my thinking about literature. Also during those years, when I was home from college, we would run into each other on the street or at the post office, where Wilson maintained a post office box while continuing to teach at the RAA.

Wilson had moved from the Bradford Building to the bottom floor of a house on Ivy Court near Fitz Henry Lane house, a house soon to be demolished during urban renewal – what Charles Olson called, “renewal by destruction.” I visited Wilson there several times but was not shown the room in which he painted, and our talk was mostly literary. Wilson was one of the most well-read artists I had met, especially in the avant-garde literature of Europe that I was also immersed in, including the novels and plays of Beckett and the “theater of absurd” plays of Eugene Ionesco, many of whose images would recur in the paintings he showed under the name of Pico Miran.

Before I left for Europe in the fall of 1959, Wilson invited me for lunch at the Gloucester Hotel. I remember that we ordered chicken croquettes, then a staple of New England cooking, and we talked long after our empty plates had been taken away. We did not correspond while I was in Italy; but immediately upon my return I looked him up again, finding him back on Main Street in an apartment located where the present courthouse and police station have since been built. Like the Bradford Building it, too, became a casualty of urban renewal. I often wondered about the effect on Wilson and his art of having repeatedly been forced to leave the spaces where he lived and worked.

During the following years, Wilson seemed to drop out of sight, though I learned that he continued to teach at the RAA and show at The Cape Ann Society of Modern Artists, until the group disbanded sometime in the late 1960s.

There is no doubt in my mind that Wilson is an important American artist. His seascapes and portraits painted under his own name compare with the finest paintings in those genres that have been exhibited on Cape Ann or elsewhere. His paintings done under the name of Pico Miran, as strange and disturbing as they may seem on first viewing, may now more than ever reflect the turbulent times – the Cold War, the nuclear threat, Korea, Vietnam – in which they were first painted, not to speak of their significance for our own age of terror and displacement.

It had long been my hope that Wilson’s work from the entire range of his singular productivity would one day be shown. From when I first encountered his paintings in the 1950s, they stimulated my thinking about the role of art in our understanding of who we are as a people and a species, and also about the remarkable person who created that work. Now, fortunately, through the generosity of the RAA&M and with the support of a committee of friends of Wilson’s legacy, including family members, this has now been made possible.

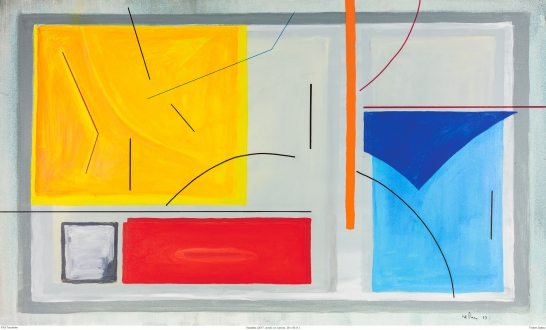

Old Ocean Was! (Winslow Wilson)

Peter Anastas, editorial director of Enduring Gloucester, is a Gloucester native and writer. His most recent book, A Walker in the City: Elegy for Gloucester, is a selection from columns that were published in the Gloucester Daily Times.