Cultural Districts, Tourism and Art

February 12, 2015

Peter Anastas

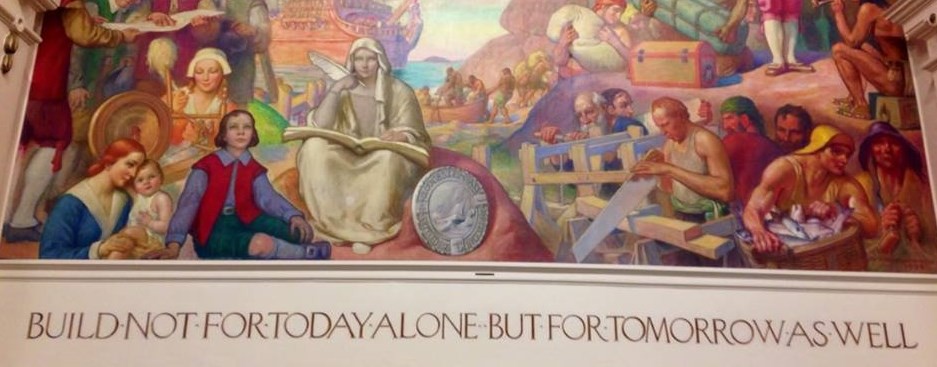

Photo provided by Document / Morin

Gloucester is now the first city in Massachusetts to have two cultural districts, with all the national and international recognition that implies, and with multiple doors open to new opportunities. The name for this new cultural district is the Gloucester Harbortown Cultural District.

All cultural districts are very special areas within municipalities and focal points of pride and collaboration. They possess an absolute “it” quality for arts & culture and sense of place.

–Massachusetts Cultural Council

Landscape with Drying Sails, 1931-32. Stuart Davis (1894-1964)

I don’t trust “cultural districts” or the thinking behind them. I believe they are just another scheme to sell out communities under the guise of supporting the arts. In Gloucester, the arts have become a way of attracting tourists, not enhancing the quality of local life for people who live here, much less supporting those who make art and need spaces to work and live in.

Cultural districts are a form of ghettoizing communities, separating the arts from other indigenous activities, mostly in the service of tourism. Monies are appropriated for the cultural districts but not for the good of the community as a whole. Case in point: Gloucester’s crown jewel, Stacy Boulevard, was allowed to languish in disrepair while money was appropriated for the Harbor Walk, which trivialized our history, and for the painted crosswalks that clashed with our redbrick, Colonial and Federal period architecture and ultimately washed away. Now comes the proposed David Black sculpture, sterile and technocratic, imposed on the city with no real process for citizen input. What’s worse is that in creating the downtown cultural district the name of the city was changed from Gloucester to Harbortown, the ultimate in trivialization and banalization.

Gloucester has a history of art richer than that of most communities. We also have a long tradition of tourism. The two should not be incompatible. We cannot and must not separate working Gloucester, which includes fishing and the industrial waterfront, from our indigenous arts, which are largely inspired and nurtured by our working port and the people it sustains. Artists like Winslow Homer and John Sloan, to give two of many possible examples, did not come here as tourists, they came to live among the people and render our life in art for the world to experience and enjoy. Our own local artists are trying to do the same thing today and we must make every effort to see that they have affordable housing and places to work, and, above all, to make Gloucester affordable to them and to natives who live and work here. A sustainable, authentic community, where people live and work in comfort, not a community that has given itself over to tourism, is the basis for a sound local economy. It is also that authenticity–real people, living real lives, in a real place–which makes visitors want to come here to experience the working landscape and the arts which it has generated.

But there is another issue that lies beneath the surface of the controversy surrounding the proposed Black sculpture. It’s not merely about its potential location, who will pay for it, why and how it was chosen, or whether we want it at all. The deeper question is one of public policy, specifically the lack of public input, not only having to do with the Black sculpture, or the vanishing crosswalks, but the way our democracy functions in Gloucester. More and more, citizens feel they have been shut out of the decisions that affect their lives, not just about art or tourism, but about the kind of community we all want to live in. At the core of this concern is not merely that people do not feel listened to or consulted, or that forums, when offered, are structured to limit citizen participation. It is the lack of planning that leaves the community vulnerable to outside influences, rather than placing crucial decisions in the hands of citizens, buttressed by a viable Master Plan that has been crafted after the widest possible citizen involvement. Gloucester’s Master Plan is out of date by fourteen years. Not only is this a breach of public policy, it is a deliberate foreshortening of the future of our city and the lives of every one of us who live here.

2. Further Thoughts on Cultural Districts

February 19, 2015

“There is simply ourselves and where we are has a particularity which we’d better use because that’s about all we got…the literal essence and exactitude of your own. I mean the streets you live on, or the clothes you wear, or the color of your own hair.”

~ Charles Olson

Evening Rocky Neck, John Sloan, 1871-1951

When I was coming of age on Rocky Neck during the 1950s, I did not think of myself as living in a “cultural district,” any more than we believed downtown Gloucester, where you could buy anything from a pair of socks to a coping saw, would one day be branded “Harbortown.”

Rocky Neck was a diverse neighborhood, many of whose residents were fishermen, or worked on the waterfront cutting and packing fish, or at the various freezers on the State Pier. Some worked at the Rocky Neck Marine Railways at the end of the Neck, caulking, painting and repairing ships, or at the Tarr and Wonson Paint Company on Horton Street, where the internationally recognized copper bottom ship’s paint had been invented and continued to be refined and produced—the company even employed a full-time chemist. There were residents who had jobs at the telephone company or in the city’s various machine shops and retail stores. Two school teachers lived on the Neck, along with the owner of a marina, a postal worker and one year-round painter, Emile Gruppe. Like in the rest of the city, there was a sense of community on Rocky Neck, which was connected by the bus line to downtown Gloucester and greater Cape Ann; just as the city was connected by train to Boston and the rest of the nation.

In the summertime there were art galleries, restaurants and antique and gifts shops. The Rockaway Hotel, a family-owned hotel whose guests arrived in June and left on Labor Day, harked back to a more genteel era of summer life in East Gloucester. In the summer, Rocky Neck also drew artists and art students from all over the country, and even from Europe. They came because of the affordable rents for studios or single rooms and for the sense of community they found. They also came, as John Sloan and Stuart Davis had come beginning in 1914, because of the proximity to the subjects they were drawn to paint—marine life, the working waterfront; ships, rocks, ocean; the beauty and density of 18th and 19th century houses crowded together on the Neck and up along Mt. Pleasant Avenue, and the people themselves, largely of Yankee heritage, with an admixture of Italian and Portuguese immigrant families, or Greeks, like my own.

Rocky Neck during my teenage years, was a melting pot of artists and craftspeople of various ethnicities and geographical backgrounds. You could hear Hungarian spoken on the deck of my father’s luncheonette, and there were two New York City school teachers, who came each summer to stay in the rooms that local residents rented out, who spoke to each other in Yiddish. Painters conversed in the languages of their countries of origins—Italian, German, Swedish, French—and at night there was a veritable “passeggiata” on Rocky Neck Avenue as natives, summer people and tourists mingled. Then, suddenly, the day after Labor Day, it was all over. Except for a few stragglers, artists mostly, who knew that the light was fantastic in early fall, or that once things had quieted down, they could do their best work, “the Island had been turned back to the Indians,” as my neighbors used to comment.

Though referred to as an art colony, Rocky Neck was much more than a place where artists came to work in a congenial, affordable environment, such as Bearskin Neck in Rockport had once been, or Provincetown, Ogunquit in Maine or Mohegan Island.

Artists were drawn to these places because of their great natural beauty and also because of the affordable housing, the congenial summer life of parties, and nights of talk among colleagues, which nurtured the art they would return to in the morning. Renowned artists like Albert Alcalay and Umberto Romano came to teach art as well as to paint, and gallery owners from the large cities opened summer annexes, so that these places also became nurturing places of art. Organizations like the Rocky Neck Art Group, the North Shore Arts Association and the Cape Ann Society of Modern Artists grew organically from the lives and needs of artists; they were not imposed on the community by government entities, using public funds, with the ultimate agenda of promoting tourism.

There were tourists, to be sure, and even some day-trippers, but most people came to stay longer than a day or two, or a week. Visitors were integrated into the community more than they are today, arriving, as many now do, on bus tours or in cruise ships and quickly spirited way on a bus to Salem, or allowed a chaperoned morning or afternoon in Gloucester, given the Harbor Walk’s virtual history of the country’s oldest seaport, told where to eat or shop, or directed to the Crow’s Nest, which they remember from the film of The Perfect Storm, except that the film did not show the real tavern, only a Hollywood mock-up on the waterfront, where the original venue is not located.

What I’m trying to indicate here is that not only Rocky Neck but the entire city, in its ethnic diversity and authenticity as a working seaport, its history as a place where artists came to live and work, eventually becoming part of the community, was, in effect, already a cultural district of great richness and did not need the tourist hype of designation or branding. What I am also trying to make clear is that once you impose these designations, this branding and commodification, on a place like Gloucester for the sole purpose of promoting it in the tourist economy, you have already begun to cheapen and degrade it, to turn its citizens into extras in a movie about a place that is no longer real but is, tragically, a simulacrum of its former reality.

3. Gloucester vs Harbortown

March 2, 2015

Peter Anastas, with writer Hyde Cox and sculptor Walker Hancock, members of the Steering Committee for the Cape Ann Festival of the Arts, Gloucester High School. 1955

As to Harbortown, it’s purely a label for a condo development scheme, having nothing to do with Art or Culture by word choice; that’s obvious. The truth is there is no artist space to rent at any price. There is certainly none that is artist-affordable. As to artists, none are moving to Harbortown or establishing themselves in cultural districts here. Just like the fishing, it is of our past more than present or future. The reasons most artists came here to work no longer exist sans the quality of light; however, what that light now shines upon, aside from nature, isn’t inspiring or compelling to the current generations of artists. The economic inequality will only increase that phenomenon. This is no longer a city where an artist can be left to be one. A bohemian life isn’t possible here without a fat trust fund and Trustafarians don’t typically create meaningful works of art. They live in places like Harbortown for the pose.

–Ernest Morin

One cannot look critically at the deleterious impact of government funded and imposed “cultural districts” on a community like Gloucester without first considering the city’s long history of indigenous art and its role in nurturing the work of artists whose reputations were based on living in Gloucester or coming here to work. Let me speak first from my own experience.

My understanding of art did not begin when we moved to Rocky Neck in June of 1951, though Rocky Neck with its rich mix of artists and marine industry, constituted a new world for my younger brother Tom and me. I was actually introduced to art in the first grade at Hovey School by the school department’s remarkable art supervisor and teacher, Hale Anthony, later known to us after her marriage as Mrs. Johnson. When we first graders initially encountered Hale Anthony, who came once a week to teach us how to draw and paint and to introduce us to art history, especially to the art that was being created around on Cape Ann, it was 1943 and I was six years old.

Local artists, including my own elementary school art teacher, Hale Anthony Johnson, delivering their paintings to the high school for the Cape Ann Festival of the Arts exhibition, 1955

I remember Hale Anthony as having an olive complexion and glossy dark hair. She dressed beautifully—“very artistically,” as our envious mothers put it—in colorful clothing, much of which she designed and made herself . We were always excited when our teachers announced that today would be the day that Mrs. Johnson was coming to do art with us because she was a lively teacher, who led us in a series of projects such as creating tiger swallowtail and monarch butterflies whose wings we would cut out of plywood or thin pine, paint with bright yellows, rust browns and blacks and glue together at ninety degree angles (their antennae made of black-stained pipe cleaners) to make them look as if they were actually in flight. Once the paint was dry, we proudly took our butterflies home, where they remained objects of pride and delight.

At Central Grammar our art teachers were Jean Nugent in seventh grade and Edna Hodgkins in eighth grade. Both were professional artists themselves, excellent painters and designers whose classrooms, hung with our drawings and paintings, always looked more like art galleries. At Gloucester High School who could ever forget studying art with the legendary painter Howard Curtis? Not only did one receive a thorough grounding in the history of art and its materials, one also had the pleasure of knowing a gifted teacher and mentor, who connected local art history to the world’s. One must also remember that when the new high school was being designed in the late 1930s, the building itself was sited to take advantage of the northern light so that its extensive art studios could receive its benefit. Gloucester thought that much of art while around us the Great Depression was still raging!

So it was not without some background in art that I arrived on Rocky Neck in June of 1951. My art education continued during the summer of 1952, when the first Cape Ann Festival of the Arts was launched. Initiated by the son of a fisherman, Joseph Grillo, the city’s first Italian-American mayor, who had been an English teacher at Gloucester High School, the festival was the largest and most panoramic celebration of local art ever mounted. It included exhibits of painting, sculpture, ceramics, crafts and weaving, along with musical, literary and dramatic events. James B. Connolly, Olympic champion and author of several highly regarded books about Gloucester fishermen, spoke at a ceremony during which his contribution to the city’s history was honored (Edo Hansen painted his portrait). The Gloucester Story by local playwright and plumber Clayton P. Stockbridge won the first Cape Ann Drama Festival Award, a cup donated by famed playwright and Annisquam summer resident Russell Crouse. Vibrant with local dialect and set aboard a Gloucester fishing vessel, the play was staged at the Gloucester School of the Little Theater on Rocky Neck. The Festival, which continued until 1962, became a summer tradition, drawing international crowds, while introducing natives to the richness of Cape Ann’s artistic heritage.

The Festival was an indigenous event, planned and funded locally. A steering committee of local residents, including artists, representatives of the business and professional communities, and students, organized the dozens of events, performances and exhibitions, with the support of the mayor’s office. There were no state or federal grants; and though the events drew people from everywhere, they were intended primarily for the benefit of the residents of Cape Ann and generously supported by local businesses. Artists organized their own events, including lectures and demonstration, and they participated jointly in mounting a massive show of art in the gymnasium at Gloucester High School, where one could experience examples of the entire range of art that was being created locally.

Art in Gloucester was as indigenous as fishing or any other industry. Just as we were given a thorough grounding in art in school, by simply living here we were equally able to experience the art that was being created locally. We were able to hear artists talking about what they did, on the street, in coffee shops or in their own studios. One did not have to leave Cape Ann to receive a comprehensive education in the making of art—painting, sculpture, theater, poetry—and its appreciation.

I do not believe for one minute that the creation of “cultural districts”—in effect, the partitioning of an organic community into ghettos, where one activity is privileged over another—could ever compare to what I have described as an indigenously created and supported culture, in which the arts are integrated into daily life as they were during the time I was nurtured, not only by art itself but by growing up in a multi-lingual, multi-ethnic city like Gloucester. We must continue this tradition. We need no help from outside. We could do it here, all of us working together—artists, citizens, public officials—because communities exist primarily for those who live in them, not for those who would impose their will or their economic, social or cultural agendas on us.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)