Charles Olson’s Call to Activism

Peter Anastas

I hate those who take away

and do not have as good to

offer.

I hate them. I hate the carelessness.

–Charles Olson

“A Scream to the Editor”

December 3, 1965

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

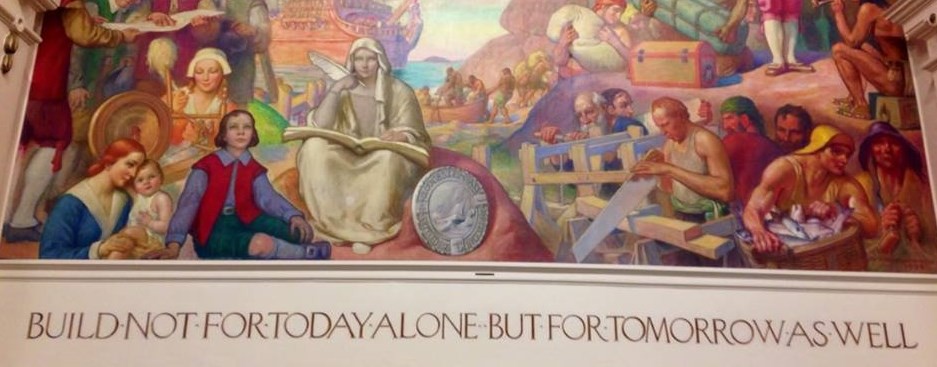

Beginning in the late 1950s and lasting for nearly a decade, the bulldozers of Urban Renewal tore through Gloucester’s 300-year-old waterfront, leveling sail lofts and net and twine manufacturers, driving ship’s chandlers and carpenters out of their shops on Duncan Street and working people from homes and tenements clustered around the Fitz Henry Lane house on Ivy Court. The Frank E. Davis fish company headquarters on Rogers Street, long thought indestructible, was knocked down, and 18th and 19th century buildings of considerable historic and architectural value in the city’s West End were also demolished.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*) Urban renewal in progress, Gloucester 1966 Photo by Mark Power

Urban renewal in progress, Gloucester 1966 Photo by Mark Power

Only one person spoke against what had been sold to the city as a panacea for our post-war economic woes. That lone voice was Charles Olson’s. Known even then, in the early 1960s, as one of the century’s most important poets, Olson, who had worked in Washington under FDR, saw clearly the implications of yet another government “revitalization” program. In letter upon letter to the editor of the Gloucester Daily Times, he called Urban Renewal “renewal by destruction,” warning the city that it was “ours to lose” if we did not stop “this renewing without reviewing,” as he characterized it.

Even when they bothered to read Olson’s passionately hortatory letters, many subscribers to Gloucester’s only newspaper thought that the nearly seven foot poet, who walked around town with a Yucatan Indian blanket wrapped around his overcoat to keep his massive frame warm, was crazy. Enraged that the Solomon Davis house on Middle Street, Gloucester’s last surviving Greek revival dwelling, was torn down by the YMCA for a basketball court that was never built, Olson composed what he called “A Scream to the Editor.” “Oh city of mediocrity and cheap ambition,” he charged in a letter that comprised the entire editorial page on December 3, 1965, “destroying its own shoulders, its own back, greedy present persons stood upon.” Olson’s imprecation would have incredible reverberations into the present.

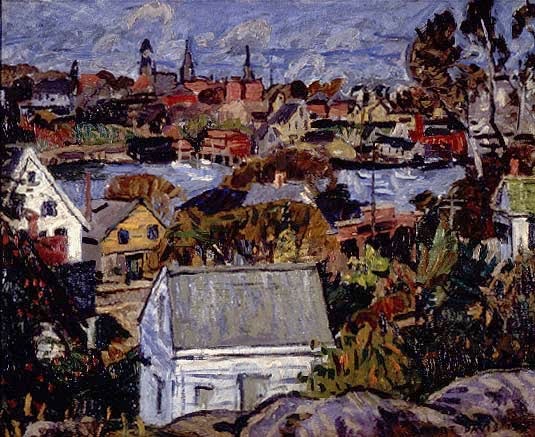

Yet during those years of destruction and loss in Gloucester, Charles Olson was practically alone in speaking out. He took the brunt of criticism from Urban Renewal’s advocates and those who were benefiting financially from a program that effectively displaced most of the families who lived along the city’s waterfront (Urban Renewal quickly became a euphemism for “relocating the poor”), leaving the Fitz Henry Lane house, built in the 1850s by the eminent Gloucester “Luminist” painter, the lone survivor of the kind of downtown wreckage that had been resisted by nearby Newburyport and Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Ironically, while those two cities have suffered more gentrification than Gloucester, they have also retained their traditional redbrick architecture and the intimate quality of their inner city neighborhoods.

Inspired by Olson’s example, a good deal of local activism since the early 1970s has been based on the preservation of a sense of place, a way of being in the world, an understanding that each place we live in has its own unique characteristics. Place, as Olson taught, is not only where we live, but also where we get our bearings from. Place is who we are and how we feel about ourselves, how we’re anchored in the world. Place is our very identity, “the geography of our being,” as Olson put it. And if we lose place, or undermine its character, whittle it away year after year through inappropriate development—chopping up neighborhoods, driving people away from the houses they were born or grew up in—we destroy the basis of our lives, if not our very identities.

Charles Olson and retired fisherman Lou Douglas talk at the kitchen table of Olson’s 28 Fort Square house

As the Australian philosopher and ecopsychologist Glenn Albrecht, has written, “People have heart’s ease when they’re on their own country. If you force them off that country, if you take them away from their land, they feel the loss of heart’s ease as a kind of vertigo, a disintegration of their whole life.” In a 2004 essay (quoted in a New York Times Magazine article of January 27, 2010, “Is There an Ecological Unconscious?”), Albrecht coined a term to describe the condition he called “solastalgia,” a combination of the Latin word solacium (comfort) and the Greek root –algia (pain), which he defined as “the pain experienced when there is recognition that the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault . . . a form of homesickness one gets when one is still at ‘home.’” Olson not only understood this condition, but he warned of its consequences in his letters and poems, thereby anticipating today’s ecopsychology movement.

Place is topography, the look and feel of the land, the mapping of streets in a town, the complex of neighborhoods; what has been built by humans or has evolved from nature. A sense of place also includes knowing the history of where we live—who inhabited it before we did and how they impressed themselves and their culture on the land. Place includes our personal and collective history as we live daily in a given town, city or region. Place concerns the life forms we cohabit with, indeed all the biota of our environment. Place is also symbol and myth; for a single town or city, the history of its founding and growth, as Thoreau believed, can be viewed as an archetype for the origin and evolution of all places on the earth.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

Charles Olson on the porch of his house at Fort Square

Considering Olson’s example, it is the responsibility of writers and artists—indeed, of all citizens— to help those who inhabit a community to understand what forces have shaped that place, what impact its history and indigenous industry have had on its character and identity, and what must be done to preserve that identity while fostering orderly economic growth and social cohesion. For Olson, Gloucester was a Polis, referring to the ancient Greek concept of a self-contained and self-governing body of citizens, a place of great cultural and linguistic diversity. Even given the depth of its history, no place can stand still. Like their inhabitants, places themselves are in continual evolution. The many committed citizens, both individuals and groups like the Gloucester Fishermen’s Wives, who have joined forces over the years to sustain our working waterfront and the integrity of our Polis, understand this. We have never advocated for “no growth,” nor have we opposed every development proposal, as some have charged. Rather, we have supported growth that we felt was sustainable and had the least deleterious impact on existing architectural and social structures in the community and on the surrounding natural environment, which comprises an essential dimension of place, indeed sustaining us all—the air we breathe and the water we drink, the woods and watershed areas that are so nourishing to us in actual as well as aesthetic ways, our natural ponds, and the ocean itself.

The longer Olson lived in his adopted city, interacting daily with its citizens, the more local the politics of this old New Dealer became. “I am a ward/ and precinct/ man myself,” Olson wrote in The Maximus Poems, “and hate/universalization” (his term for what would soon be known as “globalization.”). He had the ability to peel back the layers of time in a locale, a neighborhood, a single house even, a patch of forest, a moraine landscape, to reveal the depths and dimensions of its history. Consequently, Olson helped many of us to recognize that Gloucester was not merely the oldest fishing port in America and, as such, an archetypal place of human activity; but rather that it was a living, breathing city of 28,000 interconnected inhabitants. He also helped us to comprehend that Gloucester was a continually evolving ecosphere, and that an understanding of the rich and complex ecology of one’s home town and the woods and fields that surround it led to an understanding of the natural history, geography and ecology of what Olson called “an actual earth of value.”

Olson and Kerouac biographer Ann Charters walking on Stacy Boulevard

Olson and Kerouac biographer Ann Charters walking on Stacy Boulevard

Olson encouraged citizens to study the history of their birthplace, their region and, indeed, the nation itself, as he had, through an examination of primary documents. Court papers, land transactions in probate, property line surveys, wills and testaments and Quarterly Court records of civil litigation were, for Olson, the ur-texts of history, and as significant as the land itself for reading the passage of human habitation in given places. Maps told him more than chronological histories; though when it came to the narrative he said he found more significance in town histories, written by local historians, than in the dominant works of academic scholarship.

His theory of “saturation”—that you concentrated on one place, one writer, one topic until you had absolutely exhausted it for yourself and therefore prepared yourself henceforth to take on any subject—has proved to be immensely helpful to many of us in approaching not only the study of Gloucester, but also of larger topics in literature or history.

Olson also demonstrated that by living in a book-filled $28-dollar-a-month cold-water walkup at 28 Fort Square, on Gloucester’s waterfront, one did not need to possess material wealth in order to pursue a rewarding life. Olson counterposed himself and his ideas against the consumerist culture that was growing around us (“in the midst of plenty/walk/as close to/bare”), noting once, in the pages of the Gloucester Daily Times: “One has to have the strength of a goat, and ultimately smell as bad, to live in the immediate progress of this country.”

But Olson’s letters and poems to the editor are not mere criticism or jeremiad. They contain a wealth of historical, practical and ecological information and insight. Long before ecology became a household word and “environmentalists” were armed with wetlands protection measures, Olson, who had been a close reader of Carl Sauer’s ecological geography, was speaking out against the filling of tidelands and productive marshes. He defined ecology, in one letter, in terms of “creation as part of one’s own being,” while alluding to the impact of topology on the quality of one’s aliveness to the landscape, so that one could understand that to erase the land of its original forms and contours, either natural or man-made, would be to live a debased personal life on it. Furthermore, he showed how, if one is ignorant of one’s own history, one’s future is already circumscribed, if not blighted. And finally, he insisted in one visually stunning evocation after another—of the West End’s brick and granite architecture, the pristine marshes of Essex Avenue, the mist-shrouded banks of Mill Pond—that even though much of the city was “invisible” to her citizens as a result of the daily habit of living here and taking her extraordinary beauty for granted, the destruction of even a portion of that beauty (“the brightness which sparkles still for me, a heron, some red-winged blackbirds, several hornets sweeping down the run of that small raised path”) would constitute immeasurable loss, not only for those living now, but for “persons unknown to us in the future, who will never know what they have lost because easy contemporary ideas and persons dominate the land.”

Olson on Dogtown with poet Diane diPrima

Olson on Dogtown with poet Diane diPrima

Taken together, Olson’s letters and poems constitute a handbook for living in Gloucester in concert with her history and natural ecology. They are a call to be awakened to the morning’s light as it illuminates the “rosy red” facades of 19th century Main Street, the curve of roadways on a winter’s night, roads that follow still older, indeed aboriginal and animal paths across Cape Ann. They are a reminder, as Thoreau insisted, that no matter where we go on the face of the earth, someone has been there before us.

Deeply and specifically, Olson’s letters are a plea that we citizens recommit ourselves to our original stewardship of the land and sea, to be held in common for human use and sustenance, not to be exploited for individual profit or gain. They are an indictment of unplanned growth and development, which was beginning to occur in Gloucester during the 1950s and 60s. They speak of unnecessary change, which brings with it resentment and anger at the loss of familiar landmarks. They speak against arbitrary decisions of government to build this or destroy that, decisions which do not include those who will be affected. And they make clear, again and again, that the loss or disregard of specific local knowledge—of the land, the sea, the people, their histories and customs—leads only to a historyless future, in which Gloucester, one of the primary cities of the earth for Olson, will become “indistinguishable from/ the USA

Olson’s ghostly figure overlooks the Birdseye building before demolition.

Olson’s ghostly figure overlooks the Birdseye building before demolition.

Finally, it was Olson’s activism against Urban Renewal, against the loss of Gloucester’s historic architecture, against the filling of wetlands and all the “erosions of place,” as he called them, that helped to inspire a burgeoning grass-roots advocacy on behalf of the fishing industry and the working waterfront, the preservation of Dogtown Common, now a public conservation trust, and against overdevelopment and gentrification. For in the end, this activism— citizens acting singly or in concert on their constitutional right to make their voices heard— is about the preservation of place, not only as an idea or ideal but as a real, living, breathing community: as home and biosphere. Even as I write, Olson’s own neighborhood, the Fort section of Gloucester’s waterfront, where marine industries and residents have co-existed harmoniously for over a century, is about to undergo dramatic change. Ground has just been broken for the development of a 96-guest-room boutique hotel, said to include “an executive suite, a bridal suite, meeting rooms with state of the art audio visual equipment and two lavish ballrooms,” at the site where Clarence Birdseye invented his “flash-freezing” method for the preservation of fish. With the City’s Master Plan out of date by fourteen years, this project was undertaken in a virtual planning vacuum. Such an unconscionable lapse in planning has allowed developers to define the city and map its future, rather than the citizens themselves, creating conflict where consensus is crucial.

Like every community, Gloucester has needed the voices of citizens like Olson to remind us who we are and what we mean, both to ourselves and the world, because living here, caught up in the stresses of daily life, our home place often recedes from our awareness. As a consequence, many of us who were born or have settled here have taken Gloucester for granted. Walking the streets daily, knowing each other, working together, even arguing together, we have been given an enormous gift, the gift of community and of the ocean that surrounds and sustains us. Even if we do not fish ourselves or our families did not follow the sea, living in Gloucester, here at the ocean’s margins, we all follow the sea; and as the waterfront, which is the very heart and soul of Gloucester, stands or falls, so do we all. This is not romanticism; it’s not a nostalgic yearning for the past, as some have argued—it’s not obstructionism. It’s who we are and what we care mostly deeply about. If we lose or abandon our sense of place, allowing Gloucester, or any other significant community where people make their lives, to become like so many American towns or cities who’ve lost or abandoned their identities, or been gentrified out of existence, we will lose ourselves and everything else that matters about our lives here. As Olson warned in a letter to the Gloucester Daily Times:

Lose love

if you who live here

have not eyes to wish

for that which gone cannot

be brought back ever then

again. You shall not even miss

what you have lost. You’ll only

yourself be bereft

in ignorance of what

you haven’t even known.

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)

.jpg&container=blogger&gadget=a&rewriteMime=image%2F*)