Mary Ellen Lepionka 5/25/17

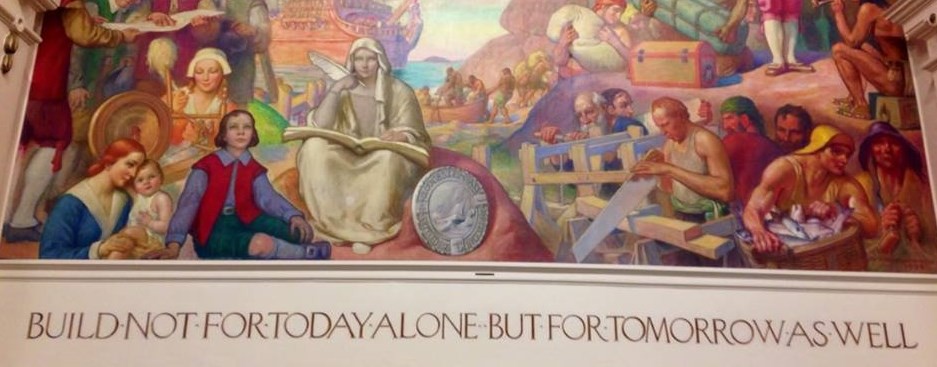

Wingaersheek Wayne Morrell (1923-2013)

In my studies of Native American history in coastal Essex County, I discovered that most translations of Native place names we have today are wrong! One reason is that early linguists referred to the wrong languages: those of southern New England. They consulted William Bradford’s notes on Pokanoket, for example, or Roger Williams’ dictionary of Narraganset, or John Eliot’s translation of the Bible into Massachuset.

But the Algonquians who lived on Cape Ann were not Pokanoket, Narraganset, or Massachuset. They were Pawtucket, relatives of the Pennacook, originally from New Hampshire and southern Maine. They spoke a dialect of Western Abenaki. According to early European explorers, except for a patois used in trading, the Pawtucket needed interpreters to speak to their neighbors to the south!

The French were the chroniclers of Abenaki and Micmac and other Algonquian languages of northern New England. But the early English linguists and historians did not consult French sources. If they had, we might have known all along what our local Native place names really mean. How hard it is to change them now! For generations, we have taken the early local scholars at their word.

Curious, I decided to use present-day reconstructions of Abenaki dialects to analyze surviving Pawtucket place names and try to determine how they really sounded and what they really mean. I started with Wingaersheek, my favorite childhood beach. I had a strong hunch that Wingaersheek was a corruption of a Native New England Algonquian word.

In his 1860 history of Gloucester John Babson claims that in 1638 when John Endicott’s surveyors asked the Indians living at the end of Atlantic Street on the Jones River Saltmarsh the name of Cape Ann, the Indians replied, “Wingaersheek”. This story has been repeated ever since. Robert Pringle, journalist and publicist, repeated it in his 1890 history. Pringle also wrote that Wingaersheek means “beautiful breaking water beach,” based on the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s faulty attempts at ethnolinguistics.

Wingaersheek would not have been the name for Cape Ann, however. It would have named the Pawtucket village there and its river and beach. (John Mason’s 1831 map of Cape Ann shows the site as Old Coffin Farm.) Algonquian place names are always about geographic features. They describe a landscape or a resource it contains, and settlements and villages associated with that landscape or resource went by the same name.

The Pawtucket also would have had a different word than Wingaersheek, which had to be an English corruption. For one thing, in the old Algonquian dialects of northern New England, the /r/ and /l/ phones were not used in speech, as noted by Europeans. Explorers at Sagadahoc on the Kennebec River noted in 1622, for example, that nobsten was the closest pronunciation for lobster that the Native Americans there seemed capable of saying.

In 1654, 1674, and 1721, Indians—undoubtedly Abenaki speakers—were reported as referring to the Merrimack River as the Monumach (or Monomack) River. Likewise, the Pawtucket name for their site near the mouth of the Annisquam River would not have included the /r/ sound at the center of Wingaersheek. The English one might, though.

Elizabethan and Tudor English speakers often added an /r/ sound to syllables ending in /a/. Listening to Yankee grandparents, for example, you may still hear that Cousin Anner had a good idear. Thus the middle syllable in Wingaersheek must have been an Englishism or an error in transcription, making it a corruption of a Pawtucket word. This gave me Wingaesheek, but that couldn’t be right either. And there was another barrier besides to understanding.

In 1895 Boston historian E. N. Horsford claimed that the name is a corruption of a seventeenth-century loan word from German Low Dutch: Wyngaerts Hoeck for “wine (or grape) garden peninsula (or land)”. The Dutch left that name on a map, in the sea off the Massachusetts coast, but I knew it could have had nothing to do with the Indians. There are too many sound shifts between Wyngaerts Hoeck and Wingaersheek, and besides, the Dutch had little or nothing to do with Cape Ann. If they had, more than one place name here would be attributable to them today.

I learned that Horsford based his claim on a 1671 map of “New Belgium” by the Dutch explorer, Arnoldus Montanus, in an etching by John Ogilby published in 1673. Montanus, in turn, based his map largely on Capt. John Smith’s 1624 map of New England, and Smith, in turn, got some of his place names from an Abenaki sachem at Saco, Maine. Wingaersheek was not among them.

Dutch Map – Montanus

I consulted all the sources from ethnolinguists who wrote about Native place names in New England and all the accounts of explorers and colonists who commented on Native language—all too numerous to list here. I also saw French sources, such as Joseph Laurent’s 1884 New familiar Abenakis and English dialogues and Jesuit missionary texts collected by Eugene Vetromille, published in 1857 as the Indian Good Book.

My proposed reconstruction of Wingaersheek as Wingawecheek is based specifically on the discovery of wechee as an Abenaki word for “ocean, sea”, found in an old lexicon, and a meaning for winka- (singular)/winga- (plural) as “a kind of sea snail or whelk,” proposed by Carol Dana of the Department of Cultural and Historic Preservation of the Penobscot (Penawahpskewi) Indian Nation, on Indian Island, Maine, in 2011, based on her participation in a Western Abenaki language revival program. I learned further that the /k/ at the end of Algonquian place names is a locative suffix, denoting place, and translates as “on”, “at”, “here” or “there” depending on context.

So now I had Winga wechee k, “Here be sea whelks,” or the like. My research suggested that the whelks in question may have been the type used to make white wampum beads. Shells certainly would have been a geographic resource worthy of an Algonquian place name. They were an important cultural and economic commodity. The coastal Algonquians used whelk shells to make white wampum beads and quahog shells to make the purple ones. Wampum was central to many social and political practices and was traded from the coast as far inland as Lake Michigan. So:

Wingaersheek = Wingawecheek

Winga = “snails, whelks”

wechee = “ocean, sea”

-k = (locative suffix)

= “Here are sea whelks (of the kind used to make white wampum)”

Aerial of Wingawecheek

Now I’m on the bridge at Goose Cove, looking across the Annisquam at the fringes of white sand and grassy dunes. Are the whelk shells I gathered in my red pail as a child still there? Now I’m on Long Wharf, looking out at the Jones River Saltmarsh. Behind me is the site of a Contact Period Native settlement. Its excavated archaeological remains lie in storage in the Harvard Peabody Museum in Cambridge. Were they the people who told Endicott’s men the name of their place? Wingawecheek must have been that name, but I’m the first to say so. And that’s the challenge of doing history, it seems: to give up what we think we know and open ourselves to new information and new interpretations, to look beyond our spatial and temporal borders—go over the bridges—to understand what’s in a name, and in the end to embrace who we really are.

PS:

- Quascacunquen (Wessacucon) = Kwaskwaikikwen: Newbury/Rowley) = “Ideal place for planting (corn)”

- Agawam (Castle Neck, Ipswich) = “Other side of the marsh”

- Chebacco (Essex) = “Separate area in between (the Ipswich and Annisquam rivers)”

- Annisquam = Wanaskwiwam (Wenesquawam/Wonasquam) = Cape Ann) = “End of the marsh”

- Winniahdin (West Parish) = “In the vicinity of the heights”

- Wamesit (Lowell, Pawtucket winter village) = “Room for all (the marsh goers)”

- Naumkeag (Nahumkeak: Beverly/Salem) = “Here are eels (to fish for)”

Mary Ellen Lepionka lives in East Gloucester and is studying the history of Cape Ann from the Ice Age to around 1700 A.D. for a book on the subject. She is a retired publisher, author, editor, textbook developer, and college instructor with degrees in anthropology. She studied at Boston University and the University of British Columbia and has performed archaeology in Ipswich, MA, Botswana, Africa, and at Pole Hill in Gloucester, MA. Mary Ellen is a trustee of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, serves on the Gloucester Historical Commission, and volunteers for Friends of Dogtown, Annisquam Historical Society, and Maud/Olson Library.

Mary Ellen Lepionka lives in East Gloucester and is studying the history of Cape Ann from the Ice Age to around 1700 A.D. for a book on the subject. She is a retired publisher, author, editor, textbook developer, and college instructor with degrees in anthropology. She studied at Boston University and the University of British Columbia and has performed archaeology in Ipswich, MA, Botswana, Africa, and at Pole Hill in Gloucester, MA. Mary Ellen is a trustee of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, serves on the Gloucester Historical Commission, and volunteers for Friends of Dogtown, Annisquam Historical Society, and Maud/Olson Library.

Wow, this is a terrific piece. I sit on my couch, looking at the beach now.Myhome is on the corner of the Annisquam, as it turns toward the bay.

About a decade ago, I spied a big piece of pottery in the mud of the marsh next to my dock. Dug it out and brought it over to a fellow on Western Ave, who is a specialist. It was an almost whole stoneware jug.it was Albany slipware, made in the 1860s

The expert told me that shellfishermen or clammers would start a fire on the shore, and sit the jug on the edge of it to warm their stew or beans or cornmeal mush, for “mug up”.

Thank you for your expertise, now I have the whole story of the name for our gorgeous beach

Oh, and I went back to the spot where the jug was mired in the mud, and FOUND the piece that had broken off….it was dark with soot. At that time, and until the fifties, folks who had cottages and camps on the shore just tossed their trash into the creek. Every spring I go out with sneakers on and gather all the glass that is exposed by the strong winter tides….

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating analysis. While I grew up on and around Wingaersheek Beach, I now live on the Penobscot River in Maine and am familiar with the impressive linguistic knowledge of the Penobscot Indian Nation. However, I wonder if the author is too quick to disregard the Dutch map name for Wingaersheek: “Wyngaert’s Hoeck”. This is the explanation we grew up with as children, and I don’t think the sound shifts are too drastic between “Wyngaert’s Hook” and “Wingaersheek”, especially when a Dutch accent is considered. Also, this would explain the presence of the “ae” – somewhat unique in the English language, but more common in Old Dutch. Also, the concord grape grows wild in the area (one of the few indigenous fruits of North America). Finally, the “hoeck” (peninsula) has been said to refer to the the long low-tide sandbar of Wingaersheek Beach which has a prominent “hook” at its end at low tide. The sandbar would be particularly relevant to note on a nautical chart as it is unique feature which has snared many mariners (past and present) and uniquely defines the Annisquam River entrance from the North… Thanks for this thought-provoking analysis of this special place!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Brilliant! Thank you…

LikeLike

Thank you so much, that was fascinating. Can’t wait to read your book. Would love to hear more if you are doing any lectures or history walks.

LikeLike

That is great detective work! I love the dissection of anglicized bastardizations, and this scratched that itch! I also love the alternate possibility in the comments.

Thanks!

LikeLike

Barner. Are you from George Barner’s line?

LikeLike

The place name “Wyngaerds Hoeck” is also found on the 1614 map of Adrien Block. The New York Public Library has a 19th century copy online.

LikeLike

Mary Ellen. Could we meet in person to talk about Gloucester 400?

LikeLike

http://www.jamesvukelich.com/blog/ojibwe-word-of-the-day-wiingashk-sweet-grass

In reading “Braiding Sweetgrass” Came across Wiingaashk defined as sweet grass. Did a search for Wingasheek bech history since I assume its names for grasses. Your blog popped up, thought Id share.

LikeLike

The Objibwe / Algonquin word for Sweetgrass is Wiingashk — so is it possible the Algonquin speaking Pawtucket were using the same word to name the dune grass or sea grass in the area?

LikeLike

What do you think of the word “wiingaashk” meaning sweetgrass as the root of Wingaersheek? YES, I am reading Braiding Sweetgrass!

LikeLike

Mary Ellen,

Great research here!!!!!! Thank You so much for this breakdown🌞🏖

♡Tara from MA

LikeLike